Creating and Saving Search for Writing Systematic Review

With a great review question and a articulate fix of eligibility criteria already mapped out, it'southward now fourth dimension to plan the search strategy. The medical literature is vast. Your squad plans a thorough and methodical search, merely yous also know that resources and interest in the project are finite. At this stage information technology might feel like you have a mountain to climb.

The bottom line? Yous volition have to sift through some irrelevant search results to find the studies that yous need for your review. Capturing a proportion of irrelevant records in your search is necessary to ensure that it identifies as many relevant records equally possible. This is the trade-off of precision versus sensitivity and, because systematic reviews aim to be equally comprehensive as possible, it is best to favour sensitivity – more is more.

By now, the size of this chore might be sounding warning bells. The skillful news is that a range of techniques and spider web-based tools can help to make searching more than efficient and save you time. We'll look at some of them every bit we walk through the four main steps of searching for studies:

- Determine where to search

- Write and refine the search

- Run and record the search

- Manage the search results

Searching is a specialist discipline and the information given here is not intended to supercede the advice of a skilled professional. Before nosotros look at each of the steps in turn, the most important systematic reviewer pro-tip for searching is:

Pro Tip – Talk to your librarian and do it early!

1. Decide where to search

It'southward of import to come with a comprehensive list of sources to search then that you don't miss annihilation potentially relevant. In clinical medicine, your first stop will likely be the databases MEDLINE, Embase, and Primal. Depending on the subject of the review, it might also exist appropriate to run the search in databases that cover specific geographical regions or specialist areas, such as traditional Chinese medicine.

In addition to these databases, you'll besides search for grayness literature (essentially, research that was not published in journals). That'south because your search of bibliographic databases will not find relevant data if it is office of, for case:

- a trials register

- a study that is ongoing

- a thesis or dissertation

- a conference abstruse.

Over-reliance on published data introduces bias in favour of positive results. Studies with positive results are more likely to be submitted to journals, published in journals, and therefore indexed in databases. This is publication bias and systematic reviews seek to minimise its effects by searching for grey literature.

2. Write and refine the search

Search terms are derived from key concepts in the review question and from the inclusion and exclusion criteria that are specified in the protocol or enquiry plan.

Keywords

Keywords will exist searched for in the title or abstract of the records in the database. They are often truncated (for example, a search for therap* to find therapy, therapies, therapist). They might also use wildcards to permit for spelling variants and plurals (for example, wom#n to discover adult female and women). The symbols used to perform truncation and wildcard searches vary by database.

Index terms

Using alphabetize terms such every bit MeSH and Emtree in a search can improve its operation. Indexers with field of study surface area expertise work through databases and tag each record with subject terms from a prespecified controlled vocabulary.

This indexing tin can save review teams a lot of time that would otherwise be spent sifting through irrelevant records. Using index terms in your search, for example, tin can help you discover the records that are actually most the topic of interest (tagged with the index term) just ignore those that contain only a brief mention of it (not tagged with the index term).

Indexers assign terms based on a careful read of each study, rather than whether or not the study contains certain words. And then the alphabetize terms enable the retrieval of relevant records that cannot exist captured by a simple search for the keyword or phrase.

Employ a combination

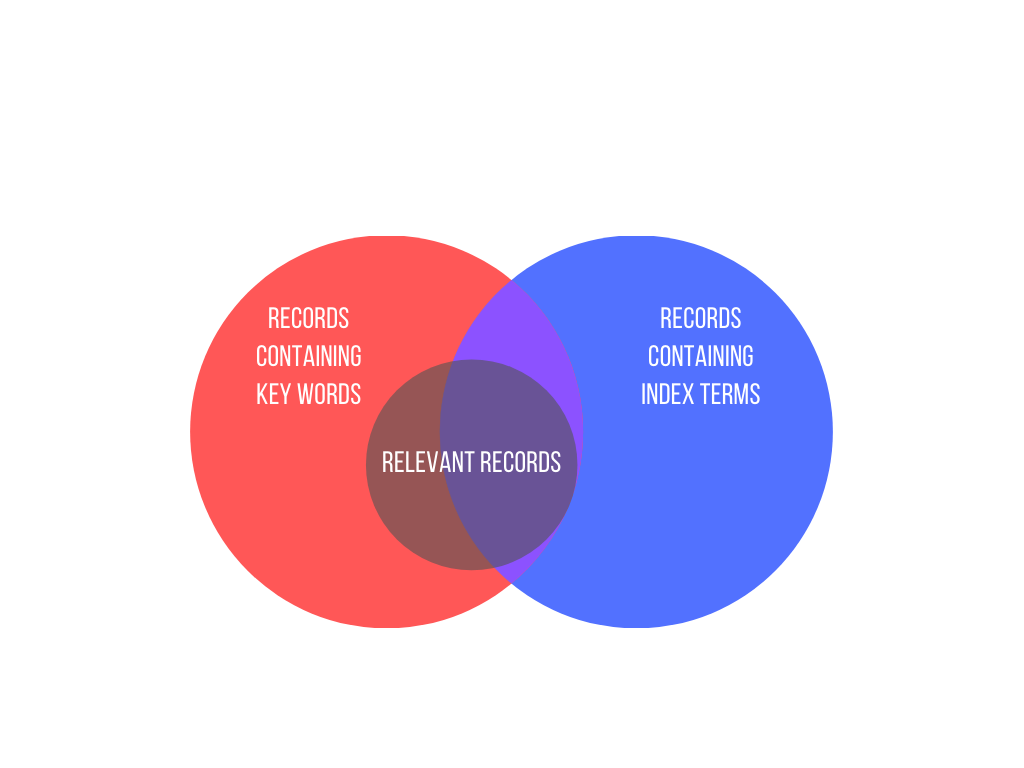

Relying solely on index terms is not appropriate. Doing and then could miss a relevant record that for some reason (indexer'due south judgment, time lag between a record beingness listed in a database and beingness indexed) has not been tagged with an index term that would enable y'all to retrieve information technology. Proficient search strategies include both index terms and keywords.

-

- Effigy 1: Combining index terms and keywords helps to brand a database search equally comprehensive as possible (Note: this is for illustrative purposes simply. The circles are not sized proportionally. You can visualise the PubMed search engine with accurate venn diagrams of your own search terms here.)

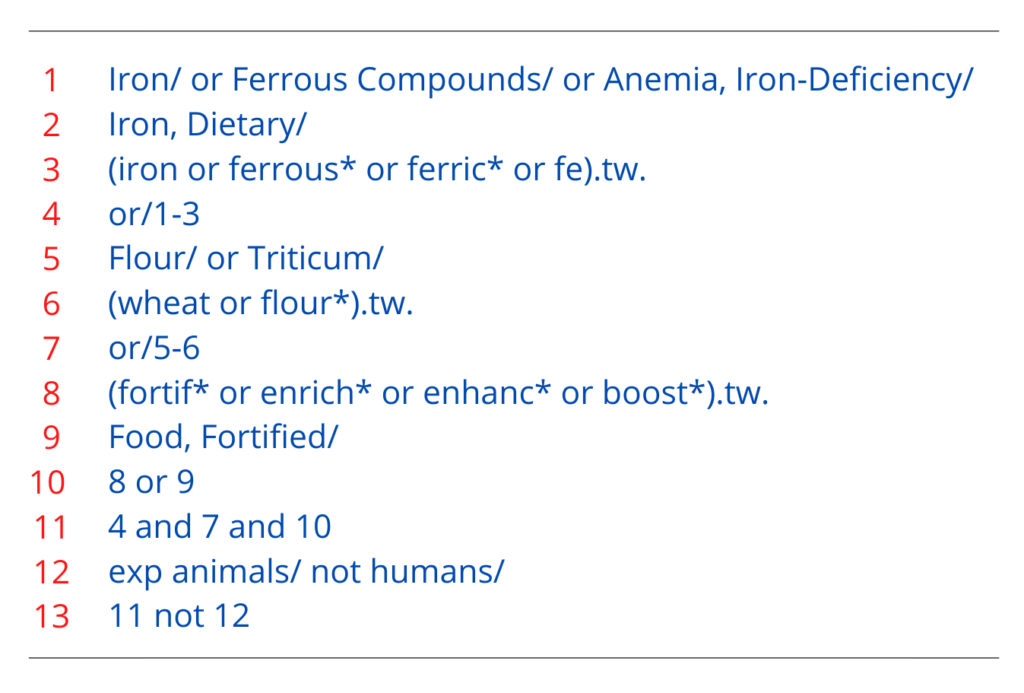

Let's see how this works in a real review! Figure 2 shows the search strategy for the review 'Wheat flour fortification with atomic number 26 and other micronutrients for reducing anaemia and improving atomic number 26 status in populations'. This strategy combines index terms and keywords using the Boolean operators AND, OR, and NOT. OR is used kickoff to reach as many records every bit possible before AND and Not are used to narrow them downwardly.

- Lines 1 and two: contain MeSH terms (denoted past the initial capitals and the slash at the end).

- Line iii: contains truncated keywords ('tw' in this context is an instruction to search the title and abstruse fields of the tape).

- Line 4: combines the 3 previous lines using Boolean OR to broaden the search.

- Line 11: combines previous lines using Boolean AND to narrow the search.

- Lines 12 and 13: further narrow the search using Boolean NOT to exclude records of studies with no human subjects.

-

- Figure 2: Example of a search strategy for MEDLINE and Medline in Progress (using the OVID platform) from a Cochrane Systematic Review.

Writing a search strategy is an iterative process. A good plan is to try out a new strategy and check that information technology has picked up the cardinal studies that you would expect it to find based on your existing noesis of the topic area. If it hasn't, you tin can explore the reasons for this, revise the strategy, check it for errors, and try it over again!

3. Run and tape the search

Because of the different ways that private databases are structured and indexed, a separate search strategy is needed for each database. This adds complexity to the search process, and it is important to keep a careful record of each search strategy equally yous run information technology. Search strategies can often be saved in the databases themselves, but information technology is a good thought to continue an offline copy as a back-up; Covidence allows you to store your search strategies online in your review settings.

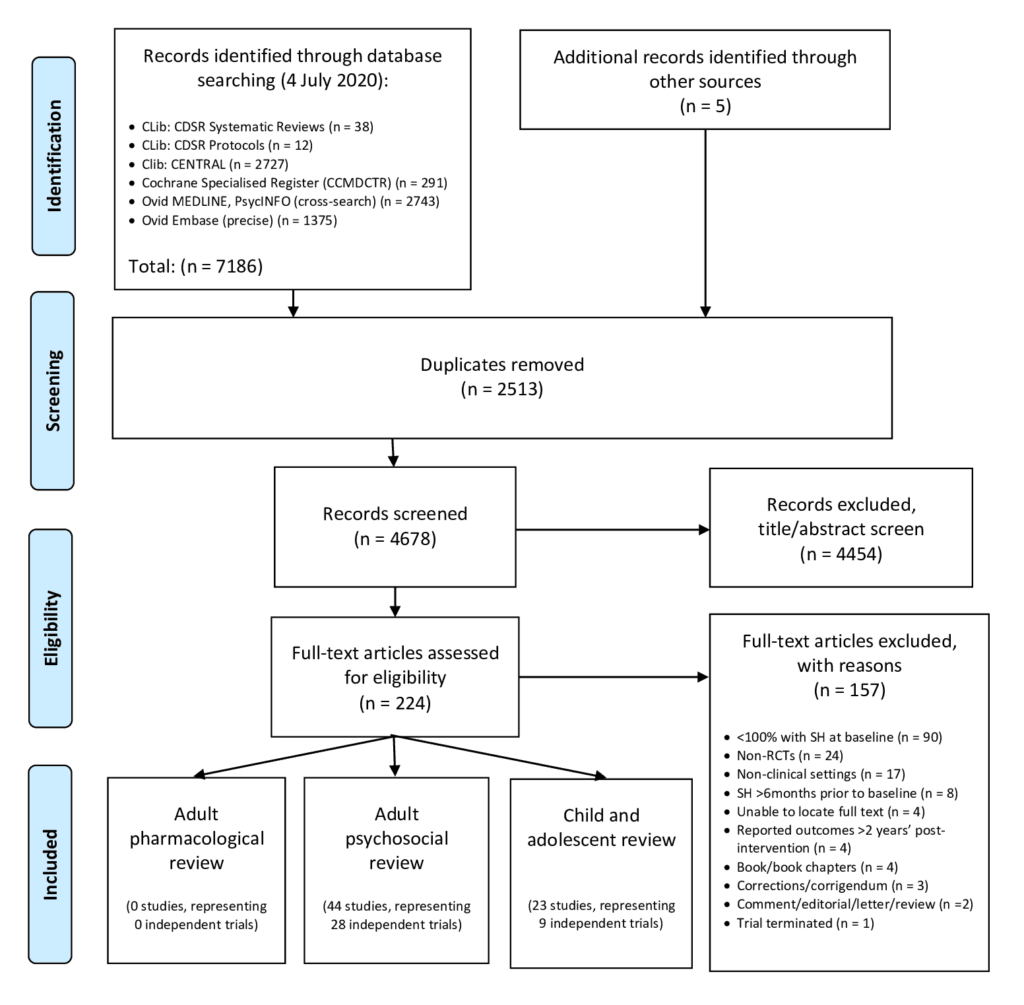

The reporting of the search will be included in the methods section of your review and should follow the PRISMA guidelines. You can download a period diagram from PRISMA's website to help you log the number of records retrieved from the search and the subsequent decisions nearly the inclusion or exclusion of studies.The PRISMA-S extension provides guidance on reporting literature searches.

-

- Figure three: Example of a PRISMA flow diagram[1].

Information technology is very important that search strategies are reproduced in their entirety (preferably using copy and paste to avoid typos) every bit part of the published review so that they tin can be studied and replicated by other researchers. Search strategies are often fabricated available equally an appendix because they are long and might otherwise interrupt the catamenia of the text in the methods section.

4. Manage the search results

Once the search is washed and you take recorded the process in enough detail to write up a thorough description in the methods department, you will move on to screening the results. This is an exciting stage in any review because it's the start glimpse of what the search strategies have found. A large volume of results may be daunting only your search is very likely to take captured some irrelevant studies considering of its loftier sensitivity, as nosotros accept already seen. Fortunately, it will be possible to exclude many of these irrelevant studies at the screening phase on the basis of the title and abstract lonely 😅.

Search results from multiple databases can be collated in a unmarried spreadsheet for screening. To benefit from process efficiencies, time-saving and easy collaboration with your team, you lot tin import search results into a specialist tool such as Covidence. A central do good of Covidence is that you can runway decisions made near the inclusion or exclusion of studies in a simple workflow and resolve conflicting decisions chop-chop and transparently. Covidence currently supports three formats for file imports of search results:

- EndNote XML

- PubMed text format

- RIS text format

If you lot'd like to attempt this feature of Covidence just don't have whatever information yet, you can download some set up-made sample data.

And you're done!

There is a lot to think about when planning a search strategy. With practice, expert assist, and the right tools your team can complete the search process with confidence.

This web log post is office of the Covidence serial on how to write a systematic review.

Sign up for a free trial of Covidence today!

fewingsthavatabot.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.covidence.org/blog/how-to-write-a-search-strategy-for-your-systematic-review/